480 BC

The importance of the battle of Salamis, first major naval battle widely documented in history, it's all in the consequences it had on politics and on the entire greek civilization.

SALAMIS

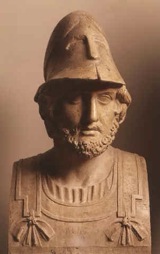

Themistocles was born in Athens between 520 and 530 BC, from a noble family. In the year 492-493 he was elected Archon for the Democratic Party's, expression of maritime business groups worried by the persian repression of the Ionian revolt, and immediately transformed the military port of Piraeus in Athens, despite the opposition of landowners, that were adversing an enlargement of trades. Themistocles was able to break free and send into exile his main opponents: Miltiades and especially Aristide, the Alcmaeonidae confidence man, known for his probity (for which he was named the righteous) and the role-perhaps magnified by the legend- he had in the battle of marathon (490). In 486, Themistocles claimed that the rents of the mines in Laurio were used for shipbuilding (483-482): thus the athenian fleet grew to 100 triremes. While Xerxes was preparing the expedition against Greece, Themistocles constitued a defensive League of all cities, except for Argos, overcoming serious difficulties, including the hostility of the sanctuary of Delphi. In 481 was at the head of the Athenian forces. After the defeat of Thermopylae, the fleet was withdrawn in the Saronic Gulf, while athenians citizens evacuated the city and ferried to Salamis.

Themistocles reject the project of transferring the fleet on the coasts of the Peloponnese and, according to tradition, secretly warned Xerxes of that project, to persuade him to give battle before Salamis. The battle, fought in September 480, was a decisive victory.

In 479 Themistocles oversaw the reconstruction of Athens, in particular the walls and the fortification of Piraeus. Later he tried to stir up a democratic revolution in the Peloponnese; but in 471, outvoted, was exiled.

From the exile he continued his political action, and perhaps considered possible an alliance with Persia, so was united to the spartan Pausanias in accusation of «medismo»; sentenced to death by the Panhellenic Assembly meeting in Lacedaemon, was welcomed by Artaxerxes, successor of Xerxes, and sent to live at Magnesia, where he died in 461.

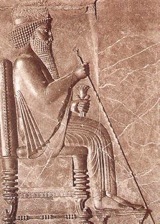

Darius's I successor was his son Xerxes I, who first put down harshly the riots erupted in Egypt and Babylon (484).

At the resumption of hostilities with Greece, Xerxes moved carefully, with a massive forces deployment. To prevent a repeat of the disaster of 490, the new King had to dig a canal North of Mount Athos and built a bridge over the Strymon; waited so that his whole army then gathered in 481, got off to Sardis, where he spent the winter. It is said that the character of Xerxes was simply obnoxious. In this regard will tell the following episodes. Because his host from Sardis had prayed him to allow to keep at home the eldest of his five sons, Xerxes order to cut in two the young man and then let the midst of his army to go between this two separated body parts. Later, he built two bridges that unite Europe to Asia: but when they were destroyed by a storm, he hangs his engineers. He built a pontoon bridge over the Hellespont and always to the sound of whip sent forward his horrified regiments from crossing.

After the successes in 480 (conquest of Central and Northern Greece, looting and burning of Athens after the victory at Thermopylae), Xerxes was finally against the ropes. With great strategy and diplomacy Themistocles was able to attract the enemy fleet in the narrow Strait between Salamis and the Attica coast and to convince the Iranians to accept the battle, which ended in a massacre and in a complete victory for the Greeks. Aeschylus, an eyewitness of the enterprise, does not hesitate to write: «I saw the Aegean cover of corpses [...] Them removed men like Tunas are knocked down, with broken oars and fragments of wood». Xerxes, with an army of 60,000 men, retreated in Asia to spend the winter and put its headquarters at Sardis. The Persian army was left in command of Mardonius to Thessaly, to resume operations in the following spring. Meanwhile, the Greeks built monuments, regulated their internal accounts and shared the booty of Xerxes himself: it's curious the fact that Themistocles, his opponent, whose behaviour was not always very clear, was showered with honors.

Unlike his father, Xerxes led a policy inspired by an intolerant Zoroastrianism. He finished the construction of Persepolis. In his later years he was involved in Palace intrigue: he died, along with his eldest son Darius, victim of a conspiracy organized by the palace prefect Artabanes instigated by another son of Xerxes, Artaxerxes I.

SALAMIS

Comapared with the city that ten years earlier had won at Marathon, Athens, which emerged victorious from the battle of Salamis and the overland campaign that followed, was a city deeply different. The construction of the fleet of Triremes had shifted the gravity centre of the foreign policy of the Athenian polis from the traditional agricultural balance in Attica, to a commercial expansion along the shipping lanes. Most of all, from the internal politics point of view, in the City-State the construction of a huge fleet, with its crowd of sailors and rowers for the first time involved in the defensive action, beyond the traditional Hoplite phalanx landowning class, had definitively shifted the balance of power in the training class.

The basics of an expansion of the Athenian democracy were all inscribed in the aftermath of the battle of Salamis and the coast of Attica in 23 September 480 BC. But even the crisis of the classical model of the poleis, that would soon explode in horrifying Peloponnesian War, could be glimpsed in those facts. The disagreements, structurally irreparable, between terrestrial and defensive strategy of Spartans and peloponnesians and Themistocles's decision to seek military solution in a naval battle, foreshadow further divergence between two models of development: the Spartan and Athenian one. The first model still tied to traditional values of the land, and for himself sentenced to replicate oligarchic government schemes; the second open to wider horizons, trade and hegemony, that sometimes border in a sort of "democratic colonialism". This divergence, ultimately could not bring that to the war and, with it, the fall of the Greek power, at the end of Greek freedom, but also to the overcoming of classicism, which reproduced, after the conquests of Alexander, changed but perhaps even more vital in the vast horizon of the Hellenistic world.

SALAMIS

After the defeat suffered by the expedition of Darius, in 490, for the Persian Empire the Greek issue had become the pivot around which revolved the entire Persian foreign policy. The defeat not only demanded a prompt repair, to be paid with the loss of credibility of the power system of the great King, but the fledgling Athenian maritime expansion policy posed problems of hegemony in the Aegean basin which, especially after the suppression of the Ionian revolt in the years before the battle of Marathon, was considered by the Persians as their exclusive commercial and military presence.

The death of Darius in 486 BC, had left on the shoulders of his son, Xerxes, the responsibility to close forever all the contends with the Greeks. Just ascended the throne, Xerxes began immediately to prepare for a new and final military operation in Greece. Following the advice of his uncle Artabanes, Xerxes realized that this time, he had to resort more than a simple punitive operation; so the Persian administration demonstrated a great organizational efficiency, collecting from all around the Empire a veritable multitude of men, from the most disparate ethnicities, to form a large army that was supposed to hit Greece.

On the opposite front, Themistocles, after confronting the Persians at the battle of Marathon, had not resigned, in the years immediately following, to see fade his drawing to give Athens a war fleet worthy of the name. According to him, in fact, was this the only means possible to try, with real chances of winning, to solve once and for all the problem constituted by the Persian threat.

Themistocles needed time to achieve its purpose; in Athens under the influence of Pro-aristocratic politics of Miltiades, he had to use all his oratorical skills even inventing a fake purpouse. The final construction of the fleet started in fact, under the pretext of a war against the neighbouring island of Aegina: to convince their fellow citizens, Themistocles used the greed and envy for the rich eginate shopping, which proved a stronger Persian menace.

The problems that Athens faced to equip itself with a fleet were, indeed, huge. Athens and Attica had not, in fact, none of the many raw materials needed for large-scale shipbuilding: wood had to come from Thrace and Macedonia, the ropes from Gaul or Iberia, pitch for caulking (hull waterproofing) from the part of Asia in the hands of the Persian enemy. Athens had an invaluable resource: the silver mines of Laurion, in which a new strand, recently discovered, had allowed the national treasure to rake in 200 talents (an attic talent was worth approximately 35 kg) of silver. To the one hundred richest citizens was granted a loan of a talent in order to build and maintain a trireme, while the other hundred talents were offered at 50 naucrarie (less affluent citizens groups), each of which would have to deal with two Triremes. So with the wealth of silver mines and an organizational structure capable of mobilising all the energy of the city, regardless of wealth, Themistocles was able to provide Athens a permanent military fleet of at least 200 Triremes; for productive organizational and media at that time it was a real record.

The next step for Themistocles was trying to create an Alliance capable of withstanding the impact of the Persian giant. but the result was under the expectations. The entire North Attica Greece, except for Thespis and the loyal Audience in Boeotia, surrendered for fear, falling in the hands of the Persians. With the Aegean Islands have long been in the hands of the great King, the Confederation was composed of 31 city: Sparta, Athens, Corinth, Megara, Aegina (which eventually, in need, the Athenians Allied), Calcis and other 25 cities not militarily significants. It was with this small force that Greece awaited Xerxes.

The Persian operations plan was simple and straightforward: the great King himself stood at the head of the army, order the construction of a bridge over the Hellespont, began to fall along the coast of Thrace and Thessaly backed up close to the fleet.

The Greeks decided to block the Persian progression at the Thermopylae pass, in the Locride Opuntia, where the Spartan King Leonidas arrived with 7,000 Hoplites, including 300 Spartans. For its part the fleet led by Themistocles, 300 Triremes, 200 of them Athenians, placed at the Strait of Artemisio between northern coast of Euboea and the Mainland. It was a well-chosen position: the two forces, naval and terrestrial ones were able to lean on each other, while the narrow pass of Thermopylae allowed the Greek Phalanx to exploit its greater shock power while the Persians, at least in a first step, had lost the advantage of superior numbers. Actually the maneuver would be effective if the disagreements and different visions of the general strategy in the Hellenic League it had, from the outset, undermined the strategic bases. The Spartans, with all Peloponnesians, were convinced that the only solution was to withdraw behind the isthmus of Corinth in the Peloponnese, and wait for the enemy; it was a myopic vision that would leave in the hands of the Persians two thirds of Greece, including Athens and Attica. In the face of protests by Themistocles, who arrived to threaten the withdrawal of Athenian ships from the allied fleet, Sparta consented to the dispatch of a contingent at Thermopylae, but the undeclared purpose was more to get the overall command of the fleet for the spartiate Euribiade, as actually occurred, that defend effectively Attica. Rejecting reinforcements and support to Leonidas, Spartans condemned the maneuver to failure and marked the fate of Leonidas and his 300 Spartans (equal) omoioi.

At first it seemed that the dual position of Thermopylae and Artemisius were defensible indefinitely; while Leonidas dismissed several enemy assaults, inflicting heavy losses and conceding relatively light, the fleet gave battle to the Persian vessels, defying a correlation of forces of one versus two, sunk several units. In fact, though, the situation was strategically untenable. Leonidas, without reinforcements, was unable to fend off the surrounding Persian maneuvers along the ridge on his left and Themistocles, unable to defend both sides of the island Euboea, risked the encirclement by the Persian fleet which, with a pretty strong contingent, could easily double the island from the East.

According to tradition, Leonidas, once knowned that a traitor (corresponding to the name of Ephialtes) had indicated to Xerxes a along the mountains to bypass the step signaled the intention to postpone Themistocles back the bulk of Hoplites staying with his Spartans for a last-ditch battle on the pitch so as to cover the retreat. Themistocles in turn knew that his position was no longer tenable; the Greek Triremes had beaten well by increasing trust in means of the fleet, but remain still so North would have been a risk of totally unnecessary.

After trying for a long time to convince Leonidas to retreat along with allied forces, Themistocles, who had never left the actual command of the fleet to the top rated Euribiade, decided to withdraw South of Attica, reluctantly leaving the Spartan king to face the fate that, from the outset, the Spartan homeland had assigned.

After the retreat of the fleet and army of towns aligned, all the poleis of Boeotia, including Thebes, were forced to open the door at the army of the great King. After a week of marching, Xerxes finally penetrated in Attica ready to avenge, once and for all, the honor of his father.

The approach of the great Persian army at Athens was forced to resort to radical measures: the defenses of the city was to be excluded because at that time Athens was not surrounded by defensive walls; at the suggestion of Themistocles, by many, not only in Athens, seen as the last hope of Hellas, the entire fleet was transferred from citizenship and the islands of Salamis and Aegina, while the fleet was fielded between the island of Salamis and the coast of Attica.

Only a few diehards were locked in the Acropolis, hoping to resist in a last bulwark against fortified, but Xerxes, after burning the town almost deserted, put an end to the last resistance massacring all the defenders of the fortress on the Acropolis.

SALAMIS

Was one of the main fighting tactics of ancient naval warfare, consisting of the approaching fleet striker in front line to the line of the fleet attacked and in violent, rapid, penetration of individual drives in the space between the one and the other enemy units trying to break through, with rostrum, as many enemy ship's oars as possible through the bump along the sides, and then, do a conversion and attack behind a boat considering the reduced ability to vogue. Defensive countermeasures to thwart the dièkplus operation, apart from the beam that protected attacked and striker, consisted, when it was possible, in deploying ships on two files in chessboard or other dual training so that the attackers, after the first breakthrough, they were exposing themselves to the risk of being spurred by the ships of the rearmost defensive line: but in order to do this it was necessary to have at least double the number of units of the enemy, otherwise it would have been easy encirclement, as have the ships on two or more lines would result in a shortening of the line of battle.

The diekplus was considered to be very effective in naval battles but required by those who used it, great superiority in the craft. In fact, the striker was to proceed with the formation on several lines leaving, between one and another and between one and the other, enough space to make free and secure the front and behind the enemy, when he could penetrate into the sides of the enemy and to smash the oars of his unit proceeded behind them, so that you can make a quick conversion back on itself, and then attack with his prue Sterns of immobilized enemy units.

The enemy, deployed in front, could perform some conversion and movement approached, but couldn't turn on themselves his units. On the other hand one must consider that if the enemy had and crews well-trained pilots, could tempt the naval tactics of the time counter, i.e. the early attack on the flank of the attacking formations in order to row: with the conversion that sailors Greeks called periplus (literally circumnavigation), for which precision maneuvering was required and great speed. If the periplus was successful, it was a disaster for the attacker, the action of diekplus left open flank to ramming or boarding the enemy.

In the periplus, or encirclement, the ships move around the wings of enemy line and twirl around the opponent, so as to reduce the scope, in preparation for an attack by the side or from behind. The ships could effectively defend stand surrounded in a circle, with the prows facing outwards and Sterns in toward the Center. And if provided by some good element onboard the ship could turn this difensive movement in an attack, as Themistocles ordered at the Artemisio.

Therefore, the diekplus was possible only in the case of a clear superiority in the navigation capacity of the attacking fleet. When it was not possible, the two fleets deploys in front, bow against bow, to be ready for the attack and to control the enemy movements, so as to prevent any freedom of manoeuvre and exclude the risk of circumvention. In such cases the naval battle came down to a bump against each other, with every effort, dependent on the single ability to maneuver, in order to turn the bow attack offensively on the sides. Or trying to make the boarding, let go the infantry on the enemy unit, possibly by preceding the attack from destructive actions with javelins, throwing stones or other weapons, so as to decrease the efficiency in enemy forces. Themistocles had already built a larger trireme, casting from the bow to the stern, where there were two small elements of bridge to the helmsman and the deal is done, a long catwalk, which deploy the Hoplites to keep them ready, wide, to boarding.

A profound change in naval tactics was introduced by the Athenian strategist Formione, in the second half of the fifth century. His exceptional qualities as Commander and Navigator is supported on crews and marine constructions in which it was stated a long experience of populations that lived nearby the sea. Formione, in some fighting, Naupactus on all, with enormous inferiority in relation to actual enemy (Corinthians in this case), ordered his units in a row, evidently feeling sure that the enemy would not dare to attack him on the side, or equally sure can quickly change their lineup as soon as this had mentioned a motion and taken to sail at full speed and more at the level of the enemy as possible. Formione waited the first gust of wind available to propel his leading ships to surround the enemy as to close them within a circle delimited by the Athenian ships, where the enemy had no chance. So bottled, the Corinthians were bowing to enemies attacks: with 20 ships against 47, Formione attacked and had easy won.

In another clash, with 20 ships against 77, Formione resorted to the anastrofe's system; the anastrofe's system was to pass the unit through the enemy lines (or rather, among the enemy vessels), causing them to suddenly turn on themselves and attacking opposing units immediately on the stem or on one of the two sides, depending on the countermanouver with which the enemy response to the anastrofe.

Skill, training, coldness, but above all the speed of the crews in the maneuvering between the opposing ships were, in the anastrofe maneuver, and even at the time of the Peloponnesian War, decisive elements, indeed unique, for determining the outcome of the fighting.

Opponents of Athens resorted to other means, developing the tactics of the onboard infantry combat, or increasing the weight and disruptive and penetrating force of prore. The syracusan forces, in a war against Athens, confident of their ability to navigators, preventing the Athenians to have at their disposal the wide open spaces of water needed for their conduct of maritime war, and forcing them to meet them in the waters of ports, transformed warships into platforms for infantry combat edge. With these innovations, the ability of the crews became less important, and the primacy of the best sailors, the Athenians in particular, began to decay.

SALAMIS

Classic rowing vessel, the trireme or triere had ancient origins. It is believed to be the development, by the Corinthians, of the two oars's order ship that had been adding a platform overboard in support of the third order of oars, and became especially in Roman and Greek navies. It was characterised by this three tiers of oars. Had, generally, a tree with square sail, but sometimes two and, more rarely, a bowsprit (in Greece). The sides of the stern were two oars-rudder and, at the extreme stern, a Pavilion for the officers. All the warships engaged in the battle of Salamis were vessels of this type. The main weapon of the trireme was a spur in oak bow, placed on the extension of the keel, sometimes in laminate bronze.

Until V century war fleets were formed by ships with 50 oars, 25 per side, called pentecontori, held in a small number of units, not fast and not very maneuverable. Before Themistocles, even after the introduction of the trireme, 40 units were the highest of the actual combined fleets by more naval centers, such as Samos. The trireme, until the introduction of the quinquereme(five orders of oars), remained the Greek warship typical, unique and constant. The hull was light, without the bridge, thinner for merchant ships, and in average was 35-40 metres long and only wide from 6 to 7 meters. The bow was very high, curved sickle-shaped, with a ram's head or other similar object in bronze. On both sides of the bow were two enormous painted eyes to keep away bad luck.

During the Peloponnesian War, the bow was reinforced with a beam perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the hull, which was going from side to side and it was coming, so as to protect the rowlocks protruding forward, in relation to the naval tactics of the time. Banks of oarsmen were not placed on three different plans; to make free the movement of the oar of each rower, they were all deployed on an equal footing, but in 'herringbone' formation, so that on each bank, sat three rowers on each side, each maneuvering an oar.

The crew was about 200 men, and the hull was not suitable for night navigation nor to support stormy waters. Then at night and trireme with malicious sea were often hosted in ports or on the beaches; in open water, with the help of a square sail, trireme could do between five and six knots of speed, while in battle were douled the sails and mast was lowered, leaving the hull only to paddlers and steersman, making it much easier and safer.

In combat, the variety of gimmicks to attack was limited. The trireme had the particularity to be pushed, by human propulsion for a short distance at speed. If the cruising speed was about 10-12 Miles per hour, it is possible that at the time of use, with the effort of the entire crew, this speed can be doubled for a few miles.

While the Persians were count on maneuverability of their Triremes, carrying groups of archers to target with arrows the enemy, the Greeks at Salamis adopted a more brutal tactics, seeking contact with the opposing ships, so to exploit, after the ramming, the contingents of Hoplites that can finally boarding the enemy vessels.

Sometimes on the Triremes were also installed war machines for throwing stones or heavy javelins against enemy ships.

SALAMIS

According to Herodotus, Xerxes assembled an army consisting of millions of men; contemporary historians such as Hanson estimate in two or three hundred thousand soldiers the force put together by Xerxes, while Delbruck estimates an amount of the total number of combatants at the disposal of the great King to a maximum of 75,000 men. We believe that an acceptable estimate of the Persian forces can get around 200,000 combatants, many of whom still serve on the accompanying fleet consisting of at least 800 Triremes in addition to auxiliary ships and transports.

It was a very considerable strength, especially for the armies of the time and, in any case, much higher than that which the Hellenes were, at best, able to field: about 10,000 Hoplites to Sparta, between 7,000 and 8,000 for Athens, much less from smaller towns; the only note of optimism for the Greeks came from the great fleet put together by Themistocles that, as we said, had a substantial Athen equipped Navy.

SALAMIS

While the fate of Athens was consummate, Themistocles had still to deal within the Allied War Council who, now more than ever, thinked as an error to give battle to the fleet or the army of the great King, and felt that the only chance for the Greeks was to attempt a resistance on the isthmus of Corinth.

Themistocles, which we think was almost to despair, acted on two floors. On one hand almost blackmailed the allies, threatening again to leave the League: "Athens might leave the Coalition", so Herodotus reminds us of the words of the Athenian strategos, "to establish a new home somewhere. The Athenians have still a city, which is today perhaps the largest of all Hellas: thier 200 Triremes! ". On other hand he was able to convince the Council of war, against the advice of Corinthians and Spartans, that only with giving battle in the narrow waters of the Strait of Salamis, considering the most seafaring experience of Hellenic ships and crews, the Greeks could cancel the advantage of numbers of the Persians, as evidenced by the collision of Artemisio.

It remained the problem to convince Xerxes to give battle at the Greek's conditions. Here is an issue of historical interpretation; looking at a map of Greece is evident, even to those who weren't totally experienced in naval strategy that Xerxes, taking advantage of naval superiority, would engage enemy ships with a portion of the fleet and landed an army, with the rest of the vessels on the coast of the Peloponnese, forcing the Greek on defensive backhand.

According to the tradition of ancient writers, Themistocles dispatched to the great King his own loyal slave who, simulating a defection, warned Xerxes that the Greek fleet was about to retire. Actually it seems unlikely that a single slave could apply directly to the King; more likely it seems that Themistocles, somehow, has managed to put this idea into the opponent's Court, counting on the fact that, as had happened at the Artemisio, the Persians entrusted in their naval superiority by not taking in consideration the hypothesis of surrounding maneuvers.

The ruse, if about ruse we can talk, had two important results: on the one hand pushed the Persians to force battle, forcing them to fight on sea chosen by Themistocles where, due to the narrowness of the channel, waters of Salamis has a width ranging from 800 to 2,000 metres, that would mean the loss of the advantage of number and advantaged the greeks greater ability to maneuver; on the other hand the ruse convinced Xerxes to send further South a part of the fleet, the Egyptian unit, to cut a hypothetical way of retreat to the Greek Triremes, reducing considerably the Persian numerical advantage. The Persians were convinced, rightly, to surprise the Greeks and gain an easy victory over an enemy already demoralized; for this, Xerxes had done install his golden throne on a hill near the sea where he would have fought the battle, so he can well enjoy the revenge on the enemy.

SALAMIS

The Persians - according to more credited estimations - sided with the fleet divided into three parts: at right, at Attica bank, were the Phoenix vessels of Sidon, Tyre and Arad, under the command of the Persian Megabazo; on the left, to Salamis, the Triremes of Ionia, Caria and Ponto under Ariabigne; while the ships of Lycia, Cilicia and the rest of the Egyptian unit occupied the Center under the command of the King's half-brother Achmene.

The Greeks faced the enemy with Euribiade on the right with the ships of Corinthians and lacedaemonians; Themistocles commanded the rest of the fleet, with the vessels of Megara and Calcis on the center and on the left, towards the coast of Attica, the homogeneous contingent of Athenian Triremes.

The Persians were trying to force the Straits, but soon they founded themselves in a real bottle and tried to recover a minimum of alignment. Instantly the two Greek wings threw themselves on the disordered enemy formation, hitting hard the Triremes of the great King.

In the narrow space, crowded by hundreds of ships, crews and specialists at the service of the Persians were unable to put to use their superior training and their greater seaworthiness.

In this great confusion a large number of Persian ships ended up being rammed and, once at close range, the contingents of Hoplites embarked on Greek Triremes were an absolutely winning weapon. Persian soldiers, stimulated by the presence of their King, fought well, but the tactical situation was very much in favour of the Greeks. Bottled and unable to maneuver, the Persian Triremes fell one by one under the blows of Greek spurs or, if addressed, suffered the attack of the heavy infantry embarked.

Casualties were very high: approximately 200 Persian Triremes sunk, while the Greeks have suggested the loss of only 42 vessels. The sea was covered with floating wreckage including sought out survivors of the Persian crews. The Athenians, still furious for the destruction of their city, distinguished themselves in the struggle not allowing mercy to the Persian sailors who sought refuge among the wreckage. Soon the battle turned into a carnage, and only a few of the Persian ships involved in the fight were able to find refuge in the escape. Xerxes did not see through his defeat, once again become clear that the outcome of the battle would have been disastrous for their fleet, he left his throne and returned, perhaps already contemplating his return to his homeland, at the Persian camp. In the first major naval battle in history, the tactical genius and the political acumen of Themistocles had assured the Greek Coalition a decisive victory; without the support of the fleet and with the supply crisis, the fate of the Persian invasion force was now decided.

SALAMIS

Aeschylus, The persians.

And a cry will be heard: «O children of Athens, move, so, come, freed the country, the brides, the children, as the Numi patri!». Arise, from our lines, a rumor of Persians accents: nor of delay was long: already the ship to the enemy ship with bronze ram beat. Was from an Hellenic vessel the first butt, that smashed a Phoenician wood; and ship against ship, who here who there, trying to manage the bows.

The great lost army tried to ruled from the beginning. But then the whole stack of wood in the Strait was cluttered, nor had mutual aid place, indeed to each other with bronze rostrum were striked, rowing orders were all crashed; and the Hellenic Woods carefully baeted them around.

Backward going the fairings: woods shattered and bloodied bodies below disappeared the sea, beach and rocks were filled with corpses; and how many ships had the barbaric horde, rowing, they were all forced to escape.

But, like tuna, or as fish in the net, barbaric were, with troncon of oars, with shrapnel and shattered, strucked by the Hellenics: and groans of death filled the clamor of the triumph, until the night gave them the rest.

But I couldn't tell you all the misfortune suffered by the Persians, even though my story lasted ten years. Once knowned that, though: a so large numbers of men in one of was never died.

SALAMIS

Defeated and humiliated, Xerxes was forced to take the way back home. He did so almost immediately, aware as it was, that after such a setback, his presence at the center of the Empire was required. The various parts of Persian power, in fact, couldn't stay long without the leadership of the King, especially when weakened by the defeat, the disintegration of the Empire itself was a concrete possibility.

In Greece the King left the army under the General Mardonius, with orders to spend the winter there and try to revival a terrestrial campaign the following year. While the fleet was in disarray towards Asia minor, King cautiously regained the Hellespont, which crossed after a month, with the whole army, excluding the Persians and the Medes that Mardonius chose to keep with him, about 50,000 fighters.

In truth, as we were saying, however still dangerous, the Persian presence in the heart of Greece was doomed to failure: without supplies, the Hellenic fleet had now taken full control of the Aegean, and Mardonius was forced to accept battle the following spring, where he was defeated and killed. Later that year, 479 BC, the Persians do not directly threaten the freedom of the Greek poleis. However, the Greece itself will be its worst menace. The rising of conflicts between the poleis, that the Persian threat only apparently postponed, blowed up in a fratricidal war. After the Peloponnesian War, the Hellenes should undergo a King's rule, but it will be a King of Hellenic language, born in the North, between the mountains of Macedonia.